Craig Martin

Prime Minister Abe Shinzo announced in April 2007 that the government was planning to establish a “panel of experts” to examine the question of whether to “revise the current interpretation of the Constitution” in order to permit Japan to engage in certain specified collective self-defense operations. The Americans have long pressed for greater Japanese involvement in collective security, and the announcement came shortly before Mr. Abe’s first trip to meet with President George W. Bush. Yet Article 9 of the Constitution of Japan, among other things, renounces “war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as a means of settling international disputes”. This has been understood by the courts and all past governments of Japan to prohibit Japan’s participation in collective self-defense operations, or engagement in any use of force, for any reason other than the direct defense of Japan.

While the government of Prime Minister Abe continues to advance the agenda for constitutional reform in order to amend Article 9, the appointment of this “panel of experts” to “re-interpret” Article 9 in a manner that would permit Japanese military participation in international collective security operations, is an effort to establish an alternate path to constitutional change as a hedge against the possible failure of the amendment process. It is an illegitimate process employing an extra-constitutional body to change the meaning of the Constitution, circumventing the legitimate amending procedure provided for in the Constitution itself, and thereby excluding the national legislature and the people of Japan from their constitutional roles in the amendment process. The “re-interpretation” sought from the “panel of experts” will likely be used to preclude interference by the judiciary, which is the branch of government that does have constitutional authority to interpret the Constitution, in the event that the resulting new policies are challenged in the courts. The “re-interpretation” sought is itself untenable, and the defense policies that it is intended to justify would be entirely inconsistent with the current language of Article 9. In short, the process has the potential to do significant harm to the integrity of Japan’s constitutional order.

The potential dangers of this process have not been sufficiently addressed in the current discussions within Japan. There has been growing discussion on the validity of this proposed process, particularly after the government announced who would be on the thirteen-man panel. But criticism has also centered on issues such as the fact that the panel is comprised almost exclusively of persons who have been publicly critical of the current restrictions on Japan’s defense posture.[1] Similarly, it has been noted that in his opening meeting with the panel, Mr. Abe made it clear that the question was “how” rather than “whether” to re-interpret the Constitution, thus pre-determining the outcome of the study.[2] But while these are certainly legitimate grounds for criticism, the discussion must go further than simply questioning the composition of the panel and the questions it is to address.

For reasons set out below, this “re-interpretation” effort ought not to be viewed as a benign process of obtaining expert advice. Given the history of timidity of Japan’s courts and the latitude they have given the government on issues relating to Article 9, and the nature of the “re-interpretation” that is being sought, the proposed “revision process” has the potential to be far more pernicious. It is an attempt by the executive to use an extra-constitutional body to alter the meaning of the Constitution without the complications of the amending process or interference by the courts. The short term results may please both Japanese and American policy makers, but this approach threatens to further weaken the integrity and normative power of the Constitution, undermine the credibility of legitimate amendment efforts, and cause misgivings among Japan’s neighbors.

Constitutional Amendment and Revision

The first and most fundamental criticism to be leveled at Mr. Abe’s proposal, is that it is essentially meaningless to speak of revising an “interpretation” of a constitution. Constitutions normally provide for the procedures to be followed and conditions to be satisfied for their amendment. As will be discussed below, the difficulty of that amending process may vary in different constitutions, but the process is typically established in the constitution itself for important reasons, and when it is so established it constitutes the only legitimate process for amending the text of the constitution. Of course, the meaning of specific provisions of the constitution will be subject to interpretation, and in most democracies it is the courts that typically are the institution with the final authority to interpret the constitution. The interpretation of certain provisions may evolve over time, as court decisions incrementally develop understandings of the language that may differ from that of earlier judgments. Such changes in interpretation, however, will typically fall within a narrow range of what is reasonably supported by the language itself. If the courts move too boldly beyond this range of possible meanings, they risk being accused of illegitimately trying to make the law rather than remaining within their appointed jurisdiction of interpreting and applying the law.

Other branches of government may develop interpretations of certain provisions of the constitution as a guide to policy making, and such interpretations may be seen as part of the “constitutional dialogue” between the various branches of government. But unless the constitution confers some specific interpretive authority to that branch, their interpretations are not to be taken as authoritative or determinative. As we will turn to in more detail below, in Japan it is quite specifically the courts that have the constitutional authority to interpret the Constitution and to determine the constitutionality of laws, policies, and other acts of government.

In short, therefore, revisions are made of the constitutional text through the process of formal amendment, while interpretation of the constitution may change incrementally through court decisions. From the perspective of constitutional legal theory, therefore, it is nonsensical to speak in lofty terms of “revising the current interpretation” of the Constitution, as though the government’s current interpretation were itself in some fashion a constitutional document or otherwise formed part of the constitutional institutions of the nation. It would be entirely different if the government was simply announcing that it was changing its policy, and that it was of the view that its changed policy was not inconsistent with its understanding of Article 9 of the Constitution. Similarly, there would be little cause for complaint if it sought the input of constitutional experts on the likely constitutionality of its proposed policy changes. But the government is doing far more than that with the establishment of this panel. It is commencing a process whereby it is expected that the “panel of experts” will produce a report that the government can hold aloft as an “expert” and “independent”, and thus authoritative, interpretation of the Constitution, one that will legitimate the policy the government seeks to pursue. As we will discuss in more detail below, this “re-interpretation” will be used to assert that the courts should defer to the “government’s discretion” on this “political question” in the event that the resulting policy is challenged in the courts. The government is in essence trying to change the meaning of the Constitution without the bother of amending it.

Constitutions contain provisions that govern the amending process for a reason. Constitutions can be viewed as pre-commitment devices that lock in certain principles and values within the political and legal structure of the nation, committing future generations of government to abide by the vision of those who framed and adopted the constitution. In that sense, the amending process is designed to make it more or less difficult for future generations to resile from those pre-commitments, or revise the vision of those who adopted the constitution. While a constitution of a country is certainly more than just the written document, it cannot be legitimate for a branch of government (particularly, in my view, the executive) to embark on attempts to change the fundamental provisions of the constitution in a manner that circumvents the amending process that the constitution itself sets out.[3] To do so is to frustrate and violate the amending procedure established in the constitution.

Some may complain that the conditions for amendment in the Constitution of Japan are particularly difficult to satisfy, but a recent comparative study of the relative difficulty of the amending processes of various constitutions suggests otherwise. The study demonstrates that both the US Constitution and the German Basic Law are examples of constitutions that are more difficult to amend than that of Japan. [4] Nonetheless, both have been amended many times. In any event, the amendment provisions constitute the revision process that the Yoshida government debated and ultimately adopted in 1947, and to the extent that there is a consensus that these conditions are too onerous, then the provisions governing the amending process should themselves be the first target of amendment. [5] But the amending procedure cannot be legitimately ignored or obviated.

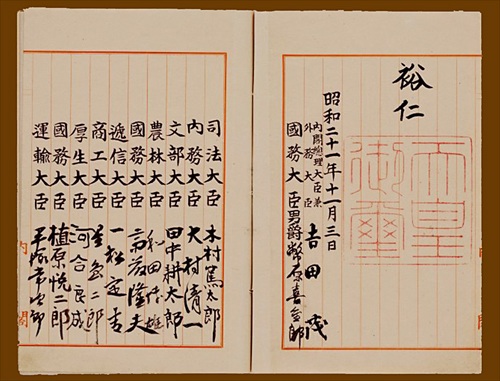

Signatures of Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru (right) and cabinet ministers on the signing page of the Constitution of Japan

The Status of the Constitution Amending Process in Japan

There has, of course, been considerable movement towards legitimate constitutional reform in Japan, which both further highlights the illegitimacy of this “re-interpretation” effort, and helps to explain why it is being pursued. As is well known, Article 96 of the Constitution of Japan provides that any amendments are to be initiated by the Diet and approved by two-thirds of each House of the Diet, and then ratified by the people through the majority of all votes cast in a referendum or special election conducted for that purpose. Despite periodic discussion of amending the Constitution, no law has been previously enacted to govern the process of ratification by the people. A new referendum law was passed by both Houses of the Diet effective May 14, 2007. Thus, while there continues to be criticism of both the content of the bill and the process by which it was passed, the legislation will come into effect in May 2010. The law requires that individual amendment proposals be voted on item by item, rather than as one package of amendments. [6] Constitutional Research Committees will be established in each House of the Diet to begin the process of research regarding possible amendments.

The establishment of this procedural framework is one further step in a movement towards amendment that has been building momentum since the 1990s. In 2000 Research Commissions on the Constitution were established in each House of the Diet, and they each submitted their final reports in the spring of 2005.[7] The LDP then published a draft of its proposed amendments in November, 2005, and this will presumably form the basis of the government’s proposals.[8] In addition to changing the title of Chapter 2 from “Renunciation of War” to “Guarantee of Security” (anzen hosho), the LDP draft proposes the deletion of the current language in Article 9(2), substituting for it a new paragraph under the sub-heading “Self Defense Military” (jieigun). The new Article 9(2) would provide that Japan will maintain a Self Defense Military, with the Prime Minister as the supreme commander, for the purpose of guaranteeing the peace, security, and independence of Japan and the Japanese people. It further provides that in its activities in the fulfillment of these functions, the Self-Defense Military shall operate pursuant to established laws, the approval of the Diet, and other such controls. In addition to performing these functions, the Self-Defense Military may also, in accordance with established law, engage in international cooperative activities to ensure the peace and security of the international society, as well as engage in such activities to defend the lives and freedoms of the people, and maintain the public order, in times of crisis. Finally, the proposed Article 9(2) provides that laws will be adopted to determine the organization and control of the Self-Defense Military.

The DPJ, the main opposition party, has not yet published an article-by-article proposal for constitutional amendment, but its “2005 Manifesto” makes clear that the DPJ also favors some form of amendment of Article 9 in order to permit Japan to engage in collective security deployments endorsed by the UN, and to cooperate with the US in developing a joint ballistic missile defense (BMD) system. It also, rather presciently, criticizes the “erosion” of the Constitution by the “arbitrary” interpretations of the Constitution by the government.[9] Thus, while there continues to be dissent in both parties, and differences between the detailed proposals that each party is likely to table, there is considerable agreement across the two parties that there is a need for some reform of Article 9.

In the end, however, the LDP may not be able to win the necessary two-thirds majority in both Houses for its proposals. It has been suggested that the manner in which the government has forced the referendum law through the Diet, with a perceived lack of debate and insufficient compromise with regard to the views of the DPJ, may polarize the issues and make passage of constitutional amendments that much more difficult.[10] Moreover, recent polls continue to reflect that support for Article 9, and a corresponding opposition to amending it, remain high within the public at large.[11] There is, therefore, a great deal of uncertainty over whether the LDP will be successful in its quest to amend Article 9. This provides the reason why the Abe government would consider laying the foundation for an alternate route to hedge against the possible failure on the amendment front, namely to “re-interpret”, and ultimately to disregard, the constraints that Article 9 places on the policies of the government.

The Panel is Extra-Constitutional

The next point to be made is that the “panel of experts” is an entirely extra-constitutional body that has no formal authority to render an interpretation of the Constitution. Again, it must be emphasized that this is not the case of a government seeking the advice of constitutional scholars over the likely constitutionality of policies it is contemplating. The evidence suggests that this is a government preparing to announce a “revised interpretation”, a new meaning of the Constitution, on the basis of an authoritative interpretation provided by a stacked “panel of experts” that has spent the summer deliberating on the question.

This development occurs against the backdrop of other recent steps towards a more robust and assertive military posture, including the upgrade of the Self-Defense Agency to full-fledged ministry status, the passage of numerous emergency and security-related laws, and increasing the levels of commitment to joint-defense with the US. Japan has recently specifically agreed to develop a BMD system in cooperation with the United States. The deployment of such a system to defend US targets is one of the specific scenarios that the “panel of experts” is to study. The inability of Japan to deploy that system in defense of non-Japan-based US targets would make it of very limited value to the US, and indeed the agreement is premised on Japanese bases intercepting ballistic missiles targeting the US. US Defense Secretary Robert Gates has recently urged the government of Japan to make a public commitment to use the system in defense of the United States.[12] The “re-interpretation” being sought is in part designed to legitimize a BMD system already agreed upon and currently under development.

The ship-based launching of an SM-3 Missile, similar to those to be deployed as part of a joint US-Japanese BMD system

From where does the authority of this “panel of experts” to engage in such “re-interpretation” arise? First, it should be noted that under the Constitution of Japan, the executive is the branch least empowered to have any say in how the Constitution is to be interpreted. Recall that the Constitution provides that the Diet is the highest organ of state (Art. 41); that the Constitution is the supreme law of the nation, and that no law, rescript, ordinance or other act of government that is contrary to the Constitution is valid (Art. 98); and that the courts are vested with the authority to interpret the Constitution and determine the constitutionality of any law, order, regulation or other official act (Art. 81).

It is not within the authority of the executive to mandate interpretations of the Constitution. But if it is not within the authority of the executive to mandate constitutional interpretations, at least the executive is a branch of government. The “panel of experts” established by the executive, to the extent that it is being called upon to provide an interpretation that will be relied upon by the government as a means of legitimizing its policies and persuading the other branches of government that the “re-interpretation” is valid and correct, has no legitimacy or authority whatsoever to engage in constitutional interpretation, and is a body not contemplated in any manner by the Constitution.

Of course, policies and laws based on new interpretations of the Constitution can be challenged in court, and so some may think that the concern being expressed here is exaggerated. But given the timidity of the courts – particularly the Supreme Court – when called upon to enforce Article 9, there is good reason to question whether the courts would step in to correct any such “re-interpretation”. Moreover, as we will discuss in the next section, there is cause for concern that the government is seeking to use this “panel of experts” to further exclude the courts from any discourse on Article 9 issues.[13]

The Legitimate Interpreters – the Courts

How has the judiciary, as the branch of government with the authority under the Constitution to interpret the Constitution, actually performed in enforcing Article 9 of the Constitution? We should begin by reviewing briefly the power of judicial review that the courts enjoy under the Constitution. As noted above, Article 81 provides that the courts are vested with the authority to interpret the Constitution and determine the constitutionality of any law, order, regulation or other act of government. In the very first case to come before it on the issue of Article 9, the Supreme Court in 1952 decided that judicial review generally was limited to ex post facto consideration of concrete cases, in the American tradition, as opposed to permitting requests, either by private litigants or the government, for determination of hypothetical questions on the constitutionality of prospective events.[14] Thus, the government cannot refer the question of whether, for example, a government policy permitting the deployment of Maritime Self Defense Force (MSDF) ships in defense of US vessels in international waters would violate Article 9, as would be possible in Germany or Canada, to name just a couple of constitutional democracies with a system that permits constitutional references.

Justices of the Supreme Court of Japan, those with the constitutional authority to interpret the Constitution

Nonetheless, the courts in countries that have followed the American model of judicial review, in which courts are limited to the consideration of concrete cases, not only function as the final guardian and interpreter of the nation’s constitution, but many have done so in a very robust fashion. The Supreme Court of the Unites States is itself a prime example. What is more, where there is no general “reference” jurisdiction of the courts, it may be argued that it is all the more important that the courts establish a broad basis for standing (that is, the criteria for permitting one to commence constitutional claims), so that concrete cases involving the constitutionality of government acts can be brought before the courts. It is precisely because the courts of Japan, particularly the Supreme Court, have so narrowed both their own jurisdiction and the basis for standing to commence constitutional claims, that one has to be concerned about the Abe government’s “re-interpretation” efforts.

There are two significant Supreme Court decisions on Article 9. In the Sunakawa case, decided in 1959, shortly before the US-Japan Security Treaty was to be renewed, the defendants to criminal proceedings for trespassing on a US Forces base challenged the constitutionality of the US-Japan Security Treaty and the presence of US military forces in Japan. Article 9(2) provides that “land, sea, and air forces as well as other war potential will never be maintained”, and the defendants argued that US Forces in Japan offended this clause. The trial court acquitted them on the basis of this argument, but the Supreme Court overturned the decision on the grounds that the status of the treaty was a “political consideration” best left to the cabinet and the legislature, and that only if government policy was “obviously unconstitutional” (whatever that means) should the courts intervene. The Court went on to comment, however, that Article 9 did not deprive Japan of the inherent right of self-defense, and that such measures or arrangements that were limited to the purpose of protecting Japan would not therefore be inconsistent with Article 9. Finally, the Court noted that the US Forces in Japan were not under the command and control of the Japanese government, and thus could not constitute military forces or “war potential” maintained by Japan so as to offend Article 9.[15] The clear implications of these comments, of course, were that actions or arrangements that were not strictly for the defense of Japan, and military forces or other war potential that were under the command of the Japanese government, might be held to be in violation of Article 9.

When the constitutionality of the SDF itself came before the Supreme Court in 1982, however, the Court again dodged the issue, and in the process narrowed the standing for claims under Article 9 to a degree that makes them all but impossible. In the Naganuma case a number of residents in Hokkaido challenged the constitutionality of the SDF and the US-Japan Security Treaty within the context of a plan to develop a missile site on a forestry reserve. They did so on the basis that the decision of the Minister of Agriculture and Forestry to convert the forestry reserve had been made for an improper purpose, and one not in the public interest; and also that they would suffer harm, both in terms of direct damage to the water table caused by the construction, and more indirect harm in that their neighborhood would be thereby transformed into a high-value target in the event of armed conflict. While their arguments were accepted by the lower court,[16] on final appeal the Supreme Court dismissed their application on the basis that none of the applicants had a direct legal interest implicated by either the decision of the Minister or the construction of the missile site, since the SDF had (after the judgment on the application by the lower court) taken special measures to ensure that there would be no harm to the water table. Thus, regardless of whether the Minister’s decision had been for an improper purpose, or whether the SDF itself existed in violation of Article 9, the applicants had no standing to make a claim.[17]

The Supreme Court has not explicitly relied upon the “political question” doctrine since the Sunakawa decision, but it has in other constitutional cases emphasized the importance of deferring to the discretion of the cabinet or legislature. Moreover, just last year it relied on the narrowest interpretation of direct legal standing as a basis for dismissing a constitutional challenge to the Prime Minister’s visits to Yasukuni Shrine.[18] It is with this history in mind that one must consider the intentions of the Abe government in establishing the “panel of experts”, and question how its “re-interpretation” will be used. The courts have so narrowed the basis for standing that virtually no one other than an SDF member ordered to deploy in some collective security operation in accordance with the new policy, would have standing to challenge the policies and laws flowing from the “re-interpretation”. In the unlikely event that a claim actually got past those preliminary hurdles, one can see how the government’s arguments to invoke the “political question” doctrine and deference to government discretion would be squarely based on how the government established the “panel of experts”. The argument would be made that not only is the question of how the government deploys its forces, in accordance with its treaty obligations to the US and under the UN Charter, entirely within the realm of politics and foreign policy rather than law, but that the government established its policy in the most careful and deliberate fashion, taking the advice of a “panel of experts” that deliberated for months on the issue before advising cabinet on its views. Thus, so the argument would run, the courts should not interfere in this complex area of governmental discretion.

In my view such an argument is not in the least bit convincing, since the question that would be before the court is in fact a purely legal one.[19] The question would be whether the actions of the government in engaging in some collective security operation, and the enabling regulations or laws pursuant to which such action was undertaken, constituted a violation of the prohibition in Article 9 against the use or threat of use of force for the purposes of settling international disputes. It is a mischaracterization to argue that the question is “political”, unless one merely means that it has political ramifications. That of course does not alter the fundamentally legal nature of the issue at hand. There are, indeed, few important constitutional questions that are not politically sensitive, or the deciding of which will not have significant political ramifications. But that does not make the question a “political question” that is therefore outside of the jurisdiction of the courts. The point, however, is that the Supreme Court of Japan has been persuaded by such arguments in the past, or perhaps more accurately, has relied upon such arguments as a cover for avoiding the risks of confrontation with the other branches of government. And the effort to develop this “re-interpretation” has to be examined in that context. In the circumstances of a weak Court and limited standing to advance claims for court interpretations of the Constitution, expert “re-interpretations” have the potential to assume an importance and an air of validity that can be exploited by the government, notwithstanding how illegitimate the exercise may be.

The “Re-Interpretation” Sought is Unreasonable

The final argument to be made against this attempt by the Abe government to “re-interpret” Article 9 is that the specific interpretation that the government seeks to obtain is simply not one that can be reasonably reconciled with the language of the Constitution. Massive amounts have been written on the interpretation of Article 9, and it is obviously an issue of considerable controversy, which we can only touch on here. But it is well to begin by recalling that Article 9 specifically provides that: (i) Japan renounces war as a sovereign right of the nation, and the use or threat of use of force as a means of settling international disputes; (ii) Japan will not maintain land, sea and air forces, as well as any other war potential; and (iii) the rights of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

The Cabinet Legislation Bureau in 1954 provided the government with an interpretation of Article 9 according to which Japan was not denied the right to self-defense under Article 9, and Japan was entitled to maintain such limited military forces that comprised the minimum necessary to defend the country against direct attack. Thus, pursuant to this understanding of Article 9, Japan could not maintain “offensive” weapons systems, or deploy forces abroad.[20] The government developed its policies in accordance with that interpretation, and as we have seen earlier, the Supreme Court obliquely acknowledged the validity of that interpretation in the Sunakawa decision.

This interpretation leads, of course, to all kinds of tortured arguments over what constitutes defensive weapons as opposed to offensive weapons, what exactly “war potential” means, and when defensive weapons systems might cross the line to become war potential.[21] But putting aside questions of whether, for instance, Japan’s Kongo Class Aegis guided-missile-system destroyers and its fleet of 16 submarines constitute offensive weapons, this is and has long been the accepted interpretation in Japan. It was departed from with the passage of legislation in 1992 to permit support activities in UN peace keeping missions, and to deploy support forces for the Afghanistan and Iraq campaigns, but the prohibition against collective self-defense remains the prevailing understanding of Article 9.[22] Thus, while Japanese SDF troops were deployed to Iraq under special legislation for “support” purposes, the troops were classified as “non-combat” and operated under strict self-defense rules of engagement, to the point that they were under the “protection” of the Australian forces.[23]

The Kirishima, one of Japan’s 4 Kongo Class Aegis guided-missile-system destroyers, and part of a fleet of 44 destroyers

It is precisely this restriction on Japanese participation in collective security operations that the Abe government wants to escape. The “panel of experts” has been asked to consider specifically such scenarios as Japanese missiles being used to intercept intercontinental ballistic missiles targeting the United States or US targets outside of Japan, and MSDF vessels engaging the naval forces of some third country in joint defense of US assets outside of Japanese territorial waters.[24] Thus, could Japanese MSDF Aegis destroyers currently deployed in the Indian Ocean engage the forces of Iran, for instance, were they to be in the process of attacking US forces in the area? Or, if Australians came under attack in Iraq, or some other country’s contingent in a UN peacekeeping mission came under attack, could the SDF troops deployed nearby engage the attackers in defense of their coalition partners? Of course, these questions, and the answers that the government is looking for, lead naturally to more significant issues governed by the same principles, such as could Japan come to the defense of US and Taiwanese forces in the event that hostilities break out with China in the Taiwan Straits? For no one should be under any illusion that the answers to the seemingly narrow questions put to the “panel of experts” will not be used to establish more general principles governing defense policy.

These scenarios would of course constitute the use of armed force in armed conflict. The SDF would be engaged in the application of deadly military force against enemy forces, for purposes that are not directly related to the defense of Japan, or in response to any attack on Japan. They would, in short, be involved in the use of force for purposes of settling international disputes, the very thing prohibited by Article 9(1). Naturally, in the context of such armed conflict Japan would expect the laws of war to apply to its forces, such that, for instance, SDF personnel would both obey and enjoy the benefits of the Geneva Conventions. Similarly, it would expect that the Hague Conventions would govern such things as the weapons that could be used against its troops. In other words, Japan would expect that it would enjoy the status of a belligerent state under international law in the event that its forces were involved in military combat as part of collective security operations. While many scholars tend to ignore or dismiss the significance of the clause stating that “the rights of belligerency shall not be recognized” in Article 9(2), belligerency is a status enjoyed under international law that triggers the application of the laws of war. There is simply no way that Article 9 can be interpreted in any reasonable fashion that is not utterly inconsistent with such armed conflict that is unrelated to a direct attack on Japan. “Re-interpreting” Article 9 to allow for Japanese forces to engage in armed conflict for the purposes of collective security, would not only render Article 9 meaningless, but would throw into question the normative power and meaning of all other provisions of the Constitution. A perverse interpretation of one provision cannot help but bleed through and influence the extent to which other provisions are taken seriously.

The reasoning behind attempts to justify “re-interpretations” that would permit such collective security operations is almost entirely result-oriented. The starting proposition is that Japan ought to be able to engage in such collective security operations, that other “normal countries” do engage in such operations, that Japan has international obligations that require it to engage in such operations, from which it follows that the most reasonable interpretation of the Constitution must be that that Japan can engage in such operations. Prime Minister Abe himself has complained that “a military alliance is an ‘alliance of blood’” and that while American troops will shed blood for Japan, “the Japanese Self Defense Forces are not asked to be prepared to shed blood when the United States comes under attack”.[24] These are certainly legitimate considerations for the debate on whether to or how to amend Article 9 of the Constitution, but they are absolutely and entirely irrelevant to how Article 9 as it currently reads is to be interpreted. Constitutional interpretation is a legal matter, not one of foreign policy or military imperatives. And as a legal matter, the “re-interpretation” that Mr. Abe wants, in order to permit Japanese troops to shed blood for the defense of others, is utterly inconsistent with any reasonable interpretation of Article 9, and is inconsistent with the closest thing to an interpretation of Article 9 that has been provided by the Supreme Court.[25]

Of course, there is already a considerable gulf between the reality of Japan’s defense posture and any reasonable reading of Article 9. While the accepted interpretation of Article 9 in Japan is that Japan is entitled to defend itself, and thus some minimal level of military force for self-defense is permitted under Article 9, the fact is that Japan’s military spending is the 4th or 5th largest in the world, (depending on how one estimates the defense expenditures of China), and it has the most sophisticated navy in Asia.[26] It is in the process of developing the two-tiered BMD system discussed above, and recent headlines reflect how threatening Russia views the deployment of similar BMD systems in Eastern Europe. It is often argued that BMD systems are not purely defensive, as they increase the vulnerability of those states whose deterrence power is thereby undermined.

The Takeshio, one of Japan’s 3 Yushio class of submarines, and part of a fleet of 16 submarines

Even if one accepts that some minimal level of defense capability is permitted, therefore, it becomes very difficult to reconcile Japan’s current military capability with the language of Article 9(2) renouncing the maintenance of military forces or other war potential. As the gulf between the constitutional norm and the reality increases, of course, the integrity and normative power of the Constitution is undermined. The great danger in the effort to develop a further “re-interpretation” that would essentially make nonsense of the constitutional provision is that it would undermine and erode the validity of the constitutional order much more broadly. If the government can ignore, or interpret out of existence, one provision, what is to stop it from so subverting any other provision? How are citizens to have any confidence in the rule of law and the value of constitutional rights if the government can, in Orwellian fashion, define constitutional norms into oblivion? Moreover, it undermines the efforts to convince both Japan’s citizens and its neighbors that the amendments proposed for Article 9 in the legitimate amending process are designed merely to allow Japan to play a more responsible role in international society as a mature constitutional democracy. If it reveals itself willing to disregard or distort existing constitutional constraints on its military power, how is anyone to take at face value the representations made by the government regarding the measured developments proposed in the amending process? Herein lie the grave dangers inherent in Mr. Abe’s announced “re-interpretation” process.

Conclusion

The Constitution of Japan has operated without amendment for a longer period than any other constitution in modern history. There are some good reasons to consider amending it now. Concerns over the growing gap between the clear language of Article 9 and the reality of Japan’s defense posture and capabilities is one. The desire to have Japan play a more active role in the international collective security system, in order to bring Japan’s defense posture more in line with its treaty obligations, and to raise its diplomatic influence to a level that is commensurate with its economic power, is another. The governing party has tabled amendment proposals, and the government has developed the legislative procedures and a timetable, for amending the Constitution. The intervening period should be used for thorough debate of the competing ideas and for careful consideration of not only whether Article 9 should be amended, but if so, precisely how it should be amended and what additional provisions may be required to ensure democratic accountability, civilian control, and other constraints on exactly how the military may be used.

If the government fails to achieve the amendments it desires, however, then it will have to accept that that is the will of the people of Japan. The government ought not to be permitted to hedge against that possibility by developing an alternate track for changing the constitutional constraints on defense policy, a process that circumvents the legitimate amending procedures and frustrates the sovereign will of the people. It is a process that appears to be designed to both exploit and further entrench the weakness of the courts when it comes to questions of Article 9, yet it is the courts that hold the legitimate authority to interpret the Constitution. It is particularly dangerous for the government to employ extra-constitutional bodies to develop new interpretations that may be used to usurp or suppress the voice of the courts in interpreting the Constitution.

Ultimately, it is not overstating the issue to say that for all these reasons, the process of changing the Constitution by “expert re-interpretation” could do serious violence to the constitutional order of Japan. And while the primary reason for opposing the process should be to prevent such harm to the constitutional order, the impact of the process on Japan’s neighbors, and thus Japan’s foreign policy, should not be overlooked. A perception (and one that is likely to be exploited by nationalists elsewhere) that Japan is re-militarizing through extra-constitutional means, and that Japan’s so-called “Pacifist Constitution” has lost its power to constrain nationalist governments, would be very destabilizing for the region, and inimical to Japan’s national security interests.

Craig Martin is a Canadian litigation lawyer who is currently working on a doctorate in law at the University of Pennsylvania, focusing on the interaction of constitutional and international law constraints on the use of armed force, and the Japanese experience with Article 9. He is also a graduate of Osaka University Graduate School of Law, where he has taught for the last four years as a visiting lecturer in comparative law. This paper expands substantially on an article published in the Japan Times on April 29, 2007, and was written for Japan Focus and posted on May 29, 2007. He can be reached at [email protected].

Notes

[1] See for example, Asahi Shinbun-International Herald Tribune, “Collective Self Defense” Editorial, April 28, 2007; “Abe’s Panel on Defense Dominated by Hawks”, Japan Times, May 6, 2007.

[2] “Abe Shapes Agenda for Defense Panel”, Asahi Shinbun – International Herald Tribune, May 19, 2007.

[3] To be perfectly fair, there is a minority view, represented by academics such as Bruce Ackerman, who do argue that a constitution can be transformed or amended through informal processes that do not conform to the amending process. But such theories have not found general acceptance in the area of constitutional law. Moreover, even Ackerman argues that such amendments are rare and only occur with a “constitutional moment” characterized by a broad based political change. There is no suggestion that Japan is undergoing any such “constitutional moment”, and indeed, as argued in the next section, it is in the process of considering formal constitutional amendment. See Bruce Ackerman, “Higher Lawmaking” in Sanford Levinson, ed. Responding to Imperfection: The Theory and Practice of Constitutional Amendment (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995). There is also some discussion among Japanese scholars of the theory of constitutional “transformation”, which has its origins in German law. See Kasuya Tomosuke, “Constitutional Transformation and the Ninth Article of the Japanese Constitution”, Paul Stephen Taylor, trans. (1986) 18:1 Law in Japan 1. It is not a generally accepted theory in Japan either.

[4] Donald S. Lutz, “Toward a Theory of Constitutional Amendment” in Sanford Levinson, ed. Responding to Imperfection: The Theory and Practice of Constitutional Amendment (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995).

[5] For a recent and outstanding account of the process of drafting, negotiating, and ultimately the debate and agreement upon the final version of the 1947 Constitution of Japan, see Ray A. Moore and Donald L. Robinson, Partners for Democracy: Crafting the New Japanese State Under MacArthur (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002)

[6] A copy of the draft bill that was passed by the Lower House in April, 2007, can be found here. The final version that was passed by the Upper House on May 14, 2007 does not appear to have been available as at May 17, 2007.

[7] Final Report of the Research Commission on the Constitution, House of Representatives, available here; and the Final Report on the Research Commission on the Constitution, House of Councillors, available here.

[8] The LDP draft proposal for Constitutional Amendment is available here. To the best of my knowledge, an official English translation has not yet been made available.

[9] Democratic Party of Japan, 2005 Manifesto, available here.

[10] See, for example, “Referendum Law Flawed”, Editorial, Asahi Shinbun-International Herald Tribune, May 14, 2007.

[11] See, for example, Ito Masami, “Article 9 in Abe’s Sights”, Japan Times, April 14, 2007;

[12] The agreement was finalized in June, 2006, though planning and development of systems had been in progress since 2003. Joseph Coleman, Associate Press, “US, Japan Expand Missile Defense Plan”, Washington Post, June 23, 006, available here. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs official announcement on the exchange of notes evidencing the agreement is available here. Japan and the US are already working on a two tiered system of BMD, employing sea launched SM3 missiles for interception of ballistic missiles while in space, and ground based Patriot Advanced Capability (PAC-3) missiles to be deployed for final-phase re-entry vehicles. Martin Seiff, UPI, “US and Japan Plan New Missile Defense Base”, Space War, December 5, 2006, available here.

[13] For a more optimistic view on the strength of the courts in this context, see John O. Haley, “Waging War: Japan’s Constitutional Constraints” (2005) 14:2 Constitutional Forum at 28. Prof. Haley argues that the Supreme Court has deferred to governmental discretion to define constitutionally permissible defense policy, but only within limits that the Court has established, particularly in the Sunakawa case.

[14] The case concerned an application made directly to the Supreme Court by Suzuki Yoshio, leader of the Socialist Party, for a declaration that the recently established Police Reserve Force (predecessor to the SDF) was unconstitutional. Supreme Court, Grand Bench, October 8, 1952, 6 Minshu 783.

[15] Sunakawa case, Supreme Court, Grand Bench, December 16, 1959, 13 Keishu 3225.

[16] Naganuma case, Sapporo District Court, September 7, 1973, 712 Hanrei Jiho 24

[17] Naganuma case, Supreme Court, September 9, 1982, 36 Minshu 1679.

[18] Yasukuni Shrine case, Supreme Court, 2nd Petty Bench, June 23, 2006. The decision emasculates the normative power of Article 20(3), which provides that the government shall not refrain from any religious activity, since under the Court’s interpretation of standing requirements, virtually no one could satisfy the “direct legal interest” requirement to challenge the government’s actions, even if they were in flagrant violation of the provision.

[19] For similar arguments in the context of questioning the continuing validity of the political question doctrine in the US, and its application by courts in constitutional challenges to the presidential war powers, see John Hart Ely, War and Responsibility: Constitutional lessons of Vietnam and Its Aftermath (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), at 55-57.

[20] For a good overview of these issues, see Richard J. Samuels, “Constitutional Revision in Japan: The Future of Article 9”, the Brookings Institution for North East Asia Policy Studies, December 15, 2004; and Richard J. Samuels, “Politics, Security Policy, and Japan’s Cabinet Legislation Bureau: Who Elected These Guys, Anyway?”, Japan Policy Research Institute, Working Paper No. 99 (March 2004) available here.

[21] For a good analysis of these arguments in the context of Japanese constitutional law, see Ashibe Nobuyoshi, Kenpo, 3rd ed. (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2002), chapter 4.

[22] See, in particular, Kokusai Rengo Heiwa Iji Katsudo-to taisuru Kyoryoku ni kansuru Horitsu, [Law Concerning Cooperation for United Nations Peace-Keeping Operations and other Operations] Law No. 79/1992, as amended by Law No. 157/2001; Heisei 13 nen 9 gatsu 11 nichi no Amerika Gasshukoku ni oite Hassei Shita Terorisuto ni yoru Kogeki-to ni Taio shite Okonawareru Kokusa Rengo Kensho no Mokuteki Tassei no tame Kokusai Rengo Ketsugi-to ni motzuku Jindoteki Sochi ni kansuru Tokubetsu Shochi-ho [The Anti-Terrorism Special Measures Law], Law No. 113/2001; and Iraku ni okeru Jindo Fukko Shien Katsudo oyobi Kakuho Shien Katsudo no Jisshi ni kansuru Tokubetsu Sochi-ho [Law Concerning the Special Measures on Humanitarian and Reconstruction Assistance in Iraq], Law No. 137/2003.

[23] See, for example, Anthony Faiola, “Japan Plans to Bring Troops Home as Iraqis Take Over”, Washington Post, June 20, 2006; Norimitsu Onishi, “Japan Commits Itself to Sending Up to 600 Ground Troops to Iraq”, New York Times, December 10, 2003; “Japan’s Troops Proceed in Iraq Without a Shot Fired”, New York Times, October 6, 2004.

[24] Fujita Naotaka, “Collective Self-Defense Panel to Study 4 Scenarios”, Asahi Shinbun – International Herald Tribune, April 28, 2007.

[25] “Collective Self-Defense” Editorial, Asahi Shinbun – International Herald Tribune, April 28, 2007.

[26] International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance, 2002-2003 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), at 332-337.

[27] Sunakawa case, supra.