Susan Brownell

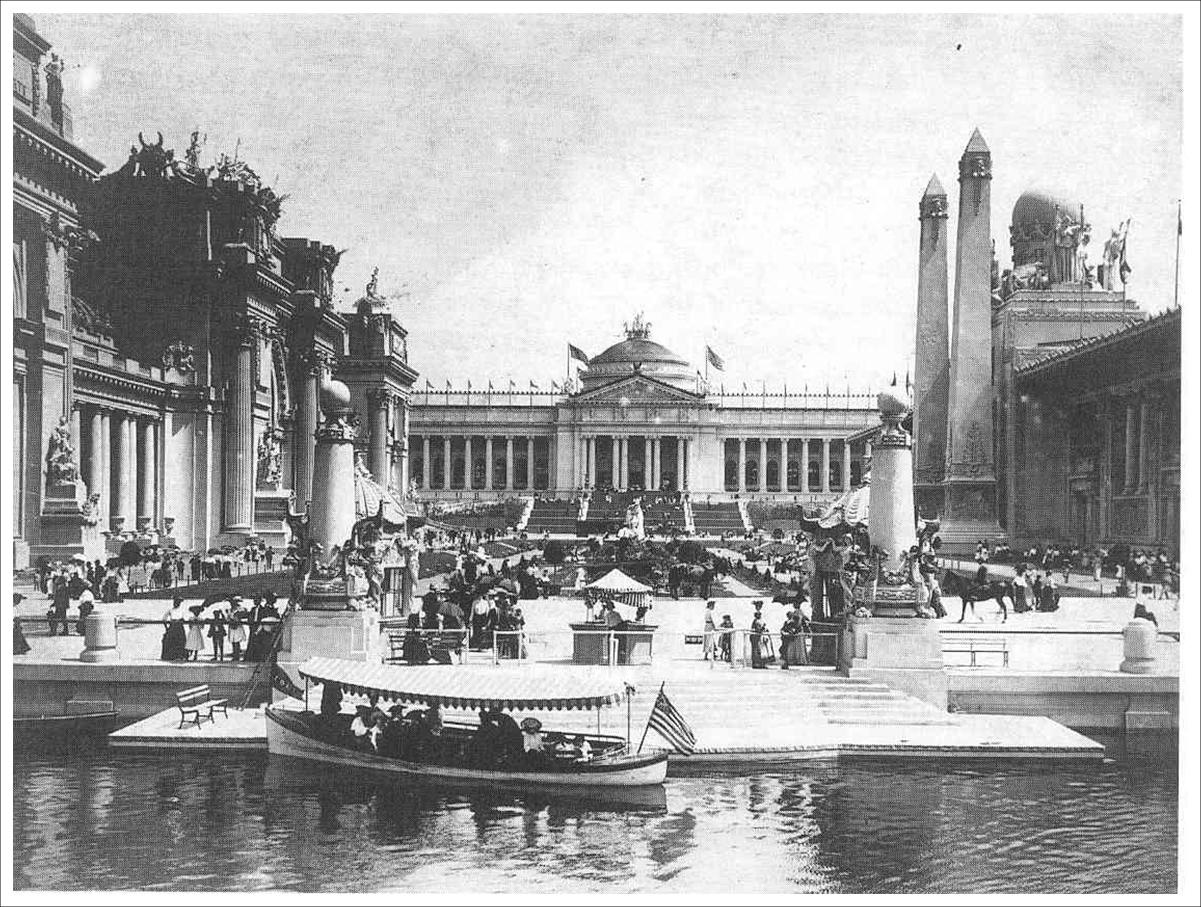

Neoclassical architecture in the Government Building at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. From David R. Francis, The Universal Exposition of 1904 (St. Louis: Louisiana Purchase Exposition Company, 1905), p. 91.

Neoclassical architecture in the Government Building at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. From David R. Francis, The Universal Exposition of 1904 (St. Louis: Louisiana Purchase Exposition Company, 1905), p. 91.

The third modern Olympic Games were held in St. Louis in 1904 alongside the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (world’s fair), and while China did not take part in the sports (it would send its first Olympic athlete to the 1932 Los Angeles Games), the Qing dynasty sent the first official delegation that it had ever sent to an international exposition. It was motivated to do so by concerns about the negative national image of China promoted by the unofficial exhibits at previous fairs, such as the opium den exhibit at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The 1904 Olympics were apparently the first Olympics to be reported in the press back in China.

Opium Den Concession at 1893 Chicago World’s Fair

Opium Den Concession at 1893 Chicago World’s Fair

The world’s fair was America’s coming-out party as a world power. It had just acquired the former Spanish colonies of the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam as a result of the Spanish-American war of 1898 and the subsequent Philippines-American war. At the fair, it presented itself as an expanding power, with an extremely large display devoted to the Philippines. Another large section of the exposition grounds was devoted to displays intended to demonstrate that the government was succeeding in civilizing American Indians.

The Philippine Constabulary Band. From The Greatest of Expositions (St. Louis: Louisiana Purchase Exposition Co., 1904), p. 226.

The Philippine Constabulary Band. From The Greatest of Expositions (St. Louis: Louisiana Purchase Exposition Co., 1904), p. 226.

That the Old World was not completely happy about the emerging New World is evident in the European criticism of the Olympic Games. IOC president Pierre de Coubertin said that awarding the Games to St. Louis had been a “misfortune” and recalled, “So the St. Louis Games were completely lacking in attraction. Personally, I had no wish to attend them. […] I had a sort of presentiment that the Olympiad would match the mediocrity of the town.” He complained about “utilitarian America.” He also labeled as “embarrassing” the Anthropology Days, in which natives who had been brought to the fair for the ethnic displays competed in some track and field events and pole-climbing, and compared their performances unfavorably with those of the “civilized” men who took part in the Olympic Games.

Ainu from Japan competing in archery contest. From the St. Louis Public Library Online Exhibit “Celebrating the Louisiana Purchase.”

Ainu from Japan competing in archery contest. From the St. Louis Public Library Online Exhibit “Celebrating the Louisiana Purchase.”

While the Americans were generally satisfied with the Olympic Games, even to this day European historians consider the St. Louis Games and the associated Anthropology Days to be one of the low points of Olympic history. It is often said that the 1906 Intermediate Olympic Games in Athens “saved” the Olympics. Historian Mark Dyreson has observed that after St. Louis it became clear that American notions of what purposes Olympic sport should serve differed quite dramatically from the notions of the European nations that made up the core of the IOC’s leadership. The conflict would continue for the rest of the twentieth century.

The first published calls for China to host the Olympic Games appeared in two YMCA publications: a 1908 essay in Tientsin Young Men, and an item in the report to the YMCA’s International Committee by C.H. Robertson, the director of the Tianjin [Tientsin] YMCA. Robertson stated that since 1907 a campaign had been carried on to inspire patriotism in China by asking three questions:

1. When will China be able to send a winning athlete to the Olympic contests?

2. When will China be able to send a winning team to the Olympic contests?

3. When will China be able to invite all the world to come to Peking [Beijing] for an International Olympic contest, alternating with those at Athens?

These three questions are now famous in China because it has taken almost exactly one hundred years for China to realize this Olympic dream.

Olympic sports were introduced into China in the late nineteenth century by the YMCA and missionary-run schools and colleges. The YMCA continued to play a major role in China’s sport system and its influence was still being felt until recently since many sports leaders were YMCA-trained. The last of these leaders passed away in recent years. The IOC co-opted the first Chinese member in 1922; he was C.T. Wang, who was active in the YMCA and a Yale University graduate. The third IOC member in China, Dong Shouyi (Tung Shou-yi) (coopted in 1947) attended Springfield College, the YMCA’s college in Massachusetts.

China imitated the St. Louis model. In 1910 the Nanyang Industrial Exposition in Nanjing was China’s first attempt at an international exposition on Chinese soil. Held in conjunction was a sporting event organized by the YMCA that later came to be known as the first national athletic games. The American YMCA used the Philippines as a launching point to spread sports throughout East Asia, and in 1913 the first Far Eastern Olympiad was held in Manila. They were so successful that the IOC was worried that they might become a rival to the Olympic Games – so it requested that the term “Olympiad” be removed, and they were thereafter called the Far Eastern Championships. They were the first regional games in the world and at various times included athletes from the Philippines, Japan, Malaysia, Indonesia, China, and Hong Kong.

One hundred four years after the U.S. hosted a world’s fair and an Olympic Games as its coming-out party, China will host the Beijing Olympic Games as its coming-out party. (Shanghai will host the World Expo in 2010). What will be on display in Beijing in 2008 will reveal the model for promoting a national image to the world that has evolved over a century in China. The Olympic slogan “One World, One Dream” expresses this ideal: we are all part of one world, and we share the dream of prosperity and strength. As the U.S. did over a century ago, China will try to display the success of its civilizing mission among its frontier minorities. It will try to display its wealth through monumental architecture and exhibitions that display its economic prowess. In 1904, train stations were one of the major ways of displaying wealth – the St. Louis Union Station completed in 1902 was one of the largest and most opulent train stations in the world. In 2008, sports stadiums have replaced train stations, and China will have its Bird’s Nest Stadium.

The St. Louis world’s fair was the biggest of all time, just as the Beijing Games may well be the biggest Olympics of all time. When a superpower holds a coming-out party, it is a hard act to follow.

Workers put the finishing touches on the National Stadium (“Bird’s Nest”). Photo by Susan Brownell, April 8, 2008.

Workers put the finishing touches on the National Stadium (“Bird’s Nest”). Photo by Susan Brownell, April 8, 2008.

The most relevant historical lesson from 1904 is that existing powers do not necessarily welcome newcomers with open arms. As happened to the U.S., there are suggestions that Chinese views about the purposes of Olympic sport conflict with the “correct” (i.e., dominant) views. It may happen that future Olympic histories written by Westerners will record that the Beijing Games were a low point in Olympic history, and London 2012 “saved” the Games.

Japan was the first East Asian nation to celebrate its emergence with an Olympic Games. The first IOC member in Japan, Kano Jigoro, was co-opted in 1909. The inventor of judo (the first non-Western sport to be included on the Olympic program), Kano established a school for Chinese students that trained 7,192 Chinese students over 13 years, including several influential reform-minded intellectuals. Japan’s coming-out party was originally scheduled for 1940, when Tokyo was due to host the Olympic Games. As described by Sandra Collins, the bid for those games was so controversial that the IOC had to postpone its vote on them for one year until 1936, because, as IOC Chairman Henri Baillet-Latour complained, “outside political disturbances created this impossible situation which ignored the rules and traditions of the IOC…” (Collins 2007, p. 95). Collins observes that the bid campaign “disrupted the IOC’s established political culture and revealed the extent to which the IOC leadership considered Japan an exotic outsider to the IOC community” (p. 90). The two years before Japan rescinded hosting rights in 1938 were surrounded by a great deal of international controversy. Inside Japan, there were debates about the degree to which the games should be oriented toward nationalistic aggrandizement or international appeasement (p. 110). Eventually, the 1940 games were cancelled because of the war

By contrast, the Olympic Games that actually took place in Tokyo in 1964 generally succeed in creating a new image of Japan as an accepted member of the international community. However, by this time, Japan was a nation that had been defeated in war, with U.S. military bases on its national territory. Japan has also hosted two Winter Games (Sapporo 1972 and Nagano 1998) that did not incite a great deal of controversy over its place in global politics. South Korea’s coming-out party at the 1988 Seoul Olympics was likewise generally successful. However, it is worth reflecting upon the fact that the Beijing Olympic Games will be the first Olympics to be staged by an Asian nation that is not host to U.S. military bases.

Kenzo Tange’s Tokyo Olympic Stadium

Kenzo Tange’s Tokyo Olympic Stadium

Linked with this 104-year history is an intellectual history relevant to the furor swirling around Tibet. These days, if it seems that Chinese ideas about national image contain some throwbacks to the turn of the last century, there is probably good reason. A widespread understanding of Tibet, which is subscribed to even by many Chinese intellectuals, is that when the central government moved in to reform its social system in the 1950s it was in the “agricultural slave society” stage, a concept drawn from Lewis Henry Morgan’s stages of civilizational progress, which were borrowed by Karl Marx. Because this conceptual framework assumes that civilizational progress is a good thing, many Chinese people cannot understand why the West criticizes the central government for leading the Tibetans toward higher civilizational stages – such as capitalism.

Indians join parade of Children of All Nations at 1904 World Exposition

Indians join parade of Children of All Nations at 1904 World Exposition

The current furor over Tibet is a good time for Western intellectuals to reflect on our own role in the situation. The ideas of social evolution and civilizational progress that entered China at the turn of the last century were powerful ideas. They formed a great symbolic system that shaped world history, in the West as well as in China.

Ainu Village at 1904 World Exposition

Ainu Village at 1904 World Exposition

After World War II there was a backlash against this schema in the West because of the extremes to which it had been taken by the Nazis. Among social scientists in the 1950s it began to be revised into a simplistic, unilinear modernization theory that still persists in some quarters today. Especially starting in the 1960s, the struggle to repudiate evolutionary schemas became heated in my own discipline of anthropology. But by this time, Chinese intellectuals were under attack, the social sciences were being dismantled, and the exchange of ideas with the West was being cut off – not to be restored until the late 1970s. Modernization theory gained a foothold, but the anti-evolution trend bypassed China. The “neo-Confucian revival” that was sparked in East Asia in the 1970s strengthened modernization theory because it only tried to describe the ways in which the Confucian tradition could facilitate modernization, and did not attempt to view critically, still less repudiate the basic schema.

The result in American anthropology was the 1970s re-shaping of the nineteenth-century schema of “progress” from “savage to barbarian to civilized” into the “levels of social complexity” of “band, tribe, chiefdom, state.” Even after 40 years, conflicts over evolutionary schemas continue to split the discipline, and there is a substantial faction of relativists opposed to social or sociobiological evolutionary schemas in any shape or form. And one must question whether in popular culture such schemas are not more dominant than in academia. The modern Olympic Games emerged out of this same late nineteenth-century intellectual milieu and reflect one of its contemporary incarnations. Today non-Greeks are attached to their connection with fictionalized ancient Greeks because they believe they are carrying on their civilization in the march of progress.

Because they are the overarching symbolic systems that still give meaning to the times in which we live, these fictions cannot easily be dismantled – in China or elsewhere. To better understand one of the underpinnings of the Tibetan ethnic conflict, Western intellectuals should be more reflective about our own intellectual history, above all the fate of American Indian civilizations. And perhaps we need to be more assertive about communicating to our Chinese colleagues the history of our post-World War II struggles with these theories.

In the global competition to establish an image as a world power, China is still trying to win by playing more or less according to the rules it learned in the early twentieth century. State leaders and common people alike are so committed to a rather simple notion of evolutionary progress based on economic modernization that they are ill-prepared to understand the nuances that have been introduced in the West. Meantime, the West has changed the rules of the game by adding new factors such as human rights. To the degree that Western ideas about what constitutes a prosperous, strong, and moral nation dominate in global politics and public opinion, the West controls the rules of the game. Of course, so long as it controls the rules it can keep changing them to ensure that newcomers never win.

This essay was originally posted on The China Beat (5-3-08). It has been revised and expanded for Japan Focus. Posted at Japan Focus on May 16, 2008.

Susan Brownell is the author of Training the Body for China, which is widely recognized as the single best scholarly work on Chinese sports. Her latest book is Beijing’s Games: What the Olympics Mean to China.

Further readings

Brownell, Susan, Beijing’s Games: What the Olympics Mean to China (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Press, 2008).

—-, ed., The 1904 Anthropology Days and Olympic Games: Sport, Race and American Imperialism (Omaha: University of Nebraska Press, forthcoming)

Collins, Sandra, “Tokyo 1940: Non-Celebres,” Andreas Niehaus and Max Seinsch (eds.), Olympic Japan: Ideals and Realities of (Inter)nationalism (Würzburg: Ergon, 2007), pp. 89-110.

Dyreson, Mark, Making the American Team: Sport, Culture and the Olympic Experience (Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1998).